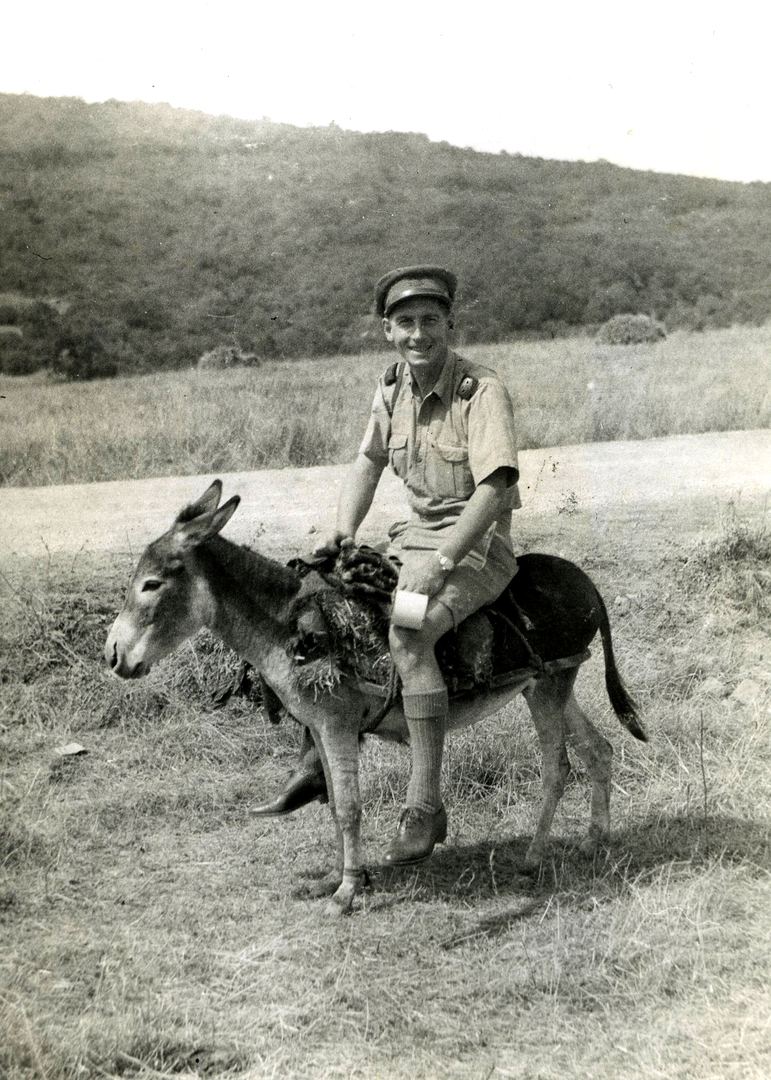

Douglas Brass

War Correspondent

When the Second World War began in September 1939, Douglas Brass was based in New Zealand as a correspondent for the Melbourne Herald and some other Australian newspapers. He covered the New Zealand scene generally but also specifically its transition to wartime conditions. After returning to Australia late in 1941, he wrote two significant columns about the New Zealand war effort.

The first, published on 25 October and headlined ‘WITH 100,000 HOME GUARDS IN ITS ARMY … New Zealand Plans To Fight Invaders’, compared New Zealand’s home defence force with that of Australia’s Volunteer Defence Corps, how it was manned and organised and how it would operate in New Zealand’s challenging physical environment.

The second, a major article titled ‘These are the New Zealanders’, appeared on 29 November, some 10 days after the beginning of the Eighth Army’s attack on German and Italian forces during Operation Crusader in Libya. The New Zealand Division played a major role in this battle near the port town of Tobruk, where Australian forces had been besieged and had won plaudits for their staunch defence. Picking up on the Australian interest in this theatre of war, Brass profiled the troops who were now ‘doing the job in Libya that the A.I.F. did a year ago’ and who had been making ‘some of the biggest news of this battle’.

In February 1942, concerned about the progress of the war, Douglas Brass enlisted with the AIF and joined the Australian artillery. In November, however, he was discharged to become accredited as an Australian correspondent with the British forces in the Middle East, initially based in Cairo. The first column under his name, ‘ROMMEL’S KORPS SECOND RATE: Old Standards Gone’, was published on 8 January 1943.